Most Men Don’t Have Real Friends (But Need Them)

Author: John Stonestreet In his article “A Photo History of Male Affection,” Brett McKay catalogs the dramatic ways male friendship has changed over...

Author: Shane Morris

Comedian John Mulaney once joked that one of Jesus’ greatest miracles was having twelve close friends in his thirties. Sadly, the modern decline of friendship is real, and anything but a punchline.

The Survey Center on American Life reports that that in 1990, almost 70% of men had five or more close friends. By 2021, just 40% reported having that many. And the number who said they had no close friends quintupled. Women haven’t fared well, either, though their friend groups haven’t shrunk as rapidly.

Part of the challenge is that time together is the oxygen of friendship. Deprive it of that, and friendship tends to die or at least become more distant. And today, perhaps due to a faster pace of life and more “stuff” piled into our schedules, spending time with friends requires more effort and intentionality than in decades past. Research shows that Americans now spend half as much time with their friends (three hours a week) as they did just a decade ago.

Writing at The Atlantic, Olga Khazan described this as a “friendship paradox.”

The typical American, it seems, texts a bunch of people “we should get together!” before watching TikTok alone on the couch and then passing out. That is, Americans have friends. We just never really see them.

And that’s not so different from having no friends.

It would be easy at this point to lecture people to get off their phones and go reconnect with someone over coffee. And to be clear, that’s not a bad idea. But Khazan doesn’t think our loneliness is entirely the fault of lazy or screen-addicted individuals. Instead, she blamed our rapidly growing isolation on the fact that we have so few regular opportunities to meet or spend time with our friends.

Echoing the theme of Robert Putnam’s 24-year-old book, Bowling Alone, Khazan pointed to the collapse of “unions, civic clubs, and religious congregations” as a major reason why people see less of each other. These so-called “third spaces” (distinct from home and work) tend to “regularize contact,” as one researcher told her. Showing up at the same time and place weekly or monthly with a lot of like-minded people makes it much more likely to form and maintain friendships.

That’s why the answer to our friendship famine can’t be, “there’s an app for that!” As Khazan pointed out, digital tech aimed at helping people form friendships has been about as successful as dating apps—which is to say, a big disappointment. This is because such techniques,

put the onus on each individual to initiate and maintain contact. Each person has to send messages and sync up schedules and find the brunch spot that will accommodate everybody’s food allergies. You can’t just show up on a Sunday and find a few hundred of your friends in the same building.

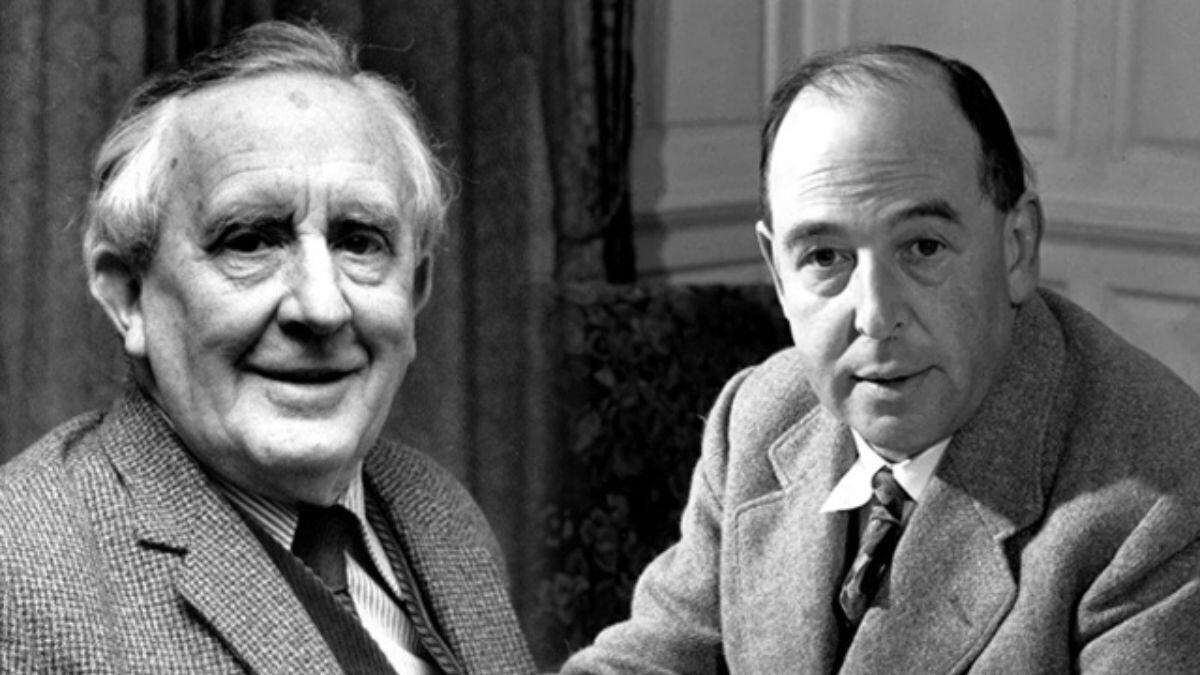

So, what is the solution? Well, the first step will be to reaffirm that friendship is not just a nice thing worth having, like a luxury vehicle or eating out weekly. It is a critical part of human flourishing. C.S. Lewis called it the “most spiritual” of the natural loves, by which he meant that no biological law compels us to make friends. Instead, we make them because we’re not mere animals:

Friendship is unnecessary, like philosophy, like art, like the universe itself (for God did not need to create). It has no survival value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival.

Judging by the damage our epidemic of loneliness has inflicted, including a rise in suicide, Lewis might not have been correct that friendship lacks survival value. It is often precisely the thing that pulls people back from the brink. That value it gives to life is one of the main reasons to take its decline so seriously.

Yet Khazan’s and Putnam’s insights mean we can’t just tell people to make friends. We must create spaces and opportunities where friendships can form and thrive.

I’ve suggested before that providing chances for young people to meet potential spouses is a call the Church should take seriously in today’s connected-but-disconnected world. The same goes for friendships. Youth groups, Christian schools, co-ops, Bible studies, and Christian colleges should emphasize making lifelong friends as one of their purposes.

The same goes for ordinary Christians who can open their homes to make up for the loss of “third spaces.” And when you do, invite not just people from your church, but those with no practicing religion who are, statistically speaking, the loneliest members of society. That kind of regular, low-pressure fellowship may be just the thing your unbelieving neighbors didn’t know they needed.

The bottom line is that Christians are people called to celebrate what’s good and restore what’s broken in the world. Friendship is one of those goods, and its decline has left people broken. Our atomized, distracted age pushes all of us, constantly, toward isolation and self-fixation. We need to be among those pushing in the opposite direction. Having a few close friends shouldn’t be considered miraculous.

Author: John Stonestreet In his article “A Photo History of Male Affection,” Brett McKay catalogs the dramatic ways male friendship has changed over...

Authors: John Stonestreet | Shane Morris Great stories often involve seemingly fortuitous but ultimately significant meetings. Lucy meets Mr. Tumnus...

Authors: John Stonestreet | Jared Hayden